Japan’s vast road network boasts 1.2 million kilometres of tarmac across its sprawling landscape.

That might sound like a lot, but it manages some 82 million vehicles in some of the world’s most densely populated cities daily. As a country, it should be at a perpetual standstill. Yet, ever since the 1950s, the Japanese have held a tiny little ace up their sleeves…

Kei-jidõsha, or ‘kei car’ as it’s more commonly known, refers to the smallest category of motor vehicles permitted to drive on Japanese roads and highways. For decades, the kei class has produced some of the most unusual-shaped vehicles anywhere in the world, powered by bike-sized engines with tyres that wouldn’t look out of place on a wheelbarrow. In an automotive landscape more bloated and overweight than ever, the Japanese kei car appears to be the cheat code required to beat the system.

This phenomenon first entered service back in 1949, after the Second World War. Japan needed to mobilise its country again, but limited resources and a weakened economy meant traditional commuter vehicles were out of reach for most people. Enter the new ‘light vehicle’ class, initially limited to a 150cc four-stroke engine (or 100cc two-stroke), followed by a larger 360cc limit in the mid-1950s. It’d take until 1958 for the first mainstream kei car to take off – Subaru’s 360 – which boasted seating for four while measuring under ten feet long.

By the 1990s, kei class engine capacity was raised to 660cc, and with manufacturers embarking on forced induction to boost power and efficiency, it soon yielded some of the most iconic models to date, including the Suzuki Cappuccino, Autozam AZ-1, and Honda Beat. There wasn’t an official limit on power, but a gentleman’s agreement capped it at 63hp. Dimensions, however, have remained the same since 1998 – no longer than 3.4m, no wider than 1.48m, and no taller than 2.0m. Kei cars don’t have to adhere to the same safety standards as non-kei cars, which is why you rarely see them sold officially outside of Japan. Not because they’re inherently dangerous, but you’d assume the Euro NCAP team wouldn’t look too favourably at your shins forming part of a front-end crumple test.

Such is their popularity that kei cars account for more than a third of all vehicle sales in Japan. But rewind to those formative years before their popularity boomed, and there was another vehicle trend emerging that made even the smallest kei cars feel like a Hummer in comparison. A class that didn’t even require a driving license to use because the 1970s would mark the launch of the even wackier world of Japanese microcars. What’s more, the driving force behind them was a manufacturer you’ll already be familiar with when it comes to building obscure, alien-like vehicles. Take a bow, Mitsuoka Motor.

Before Mitsuoka spent their days transforming K11 Micras into AI-generated Jaguar Mark IIs, its business centred around importing and servicing European cars for customers across Japan. Founder Susumu Mitsuoka always dreamt of creating his own vehicles, but it wasn’t until the late ’70s that he was able to do so. When a customer brought their Italian microcar in for repairs – a Casalini Sulky – Mitsuoka-san was left frustrated that he couldn’t find the parts required to fix it. Rather than give up, Mitsuoka-san adopted the optimistic Speedhunters attitude and declared how hard can it be? Several years later, in 1982, Mitsuoka’s first complete car was born – the BUBU Shuttle-50.

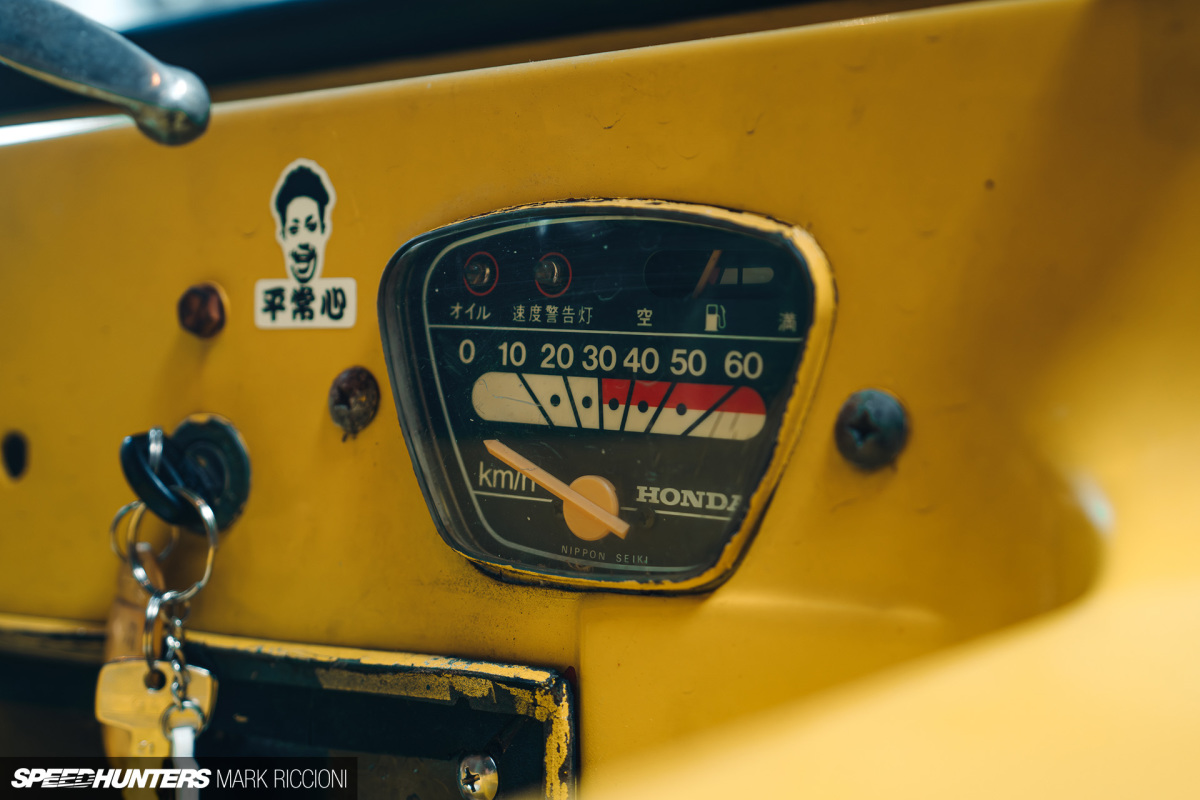

To call the BUBU Shuttle-50 a car by modern standards might be pushing it, though it does have doors, wing mirrors, and a windscreen. Its engine measured just 50cc, driving a single wheel at the rear, with two further wheels up front doing the steering. But this wasn’t Mitsuoka being weird for the sake of it; its goal was to mobilise all Japanese people. Thanks to its 50cc engine with steering, throttle, and braking controlled by handlebars, the BUBU Shuttle-50 only needed a moped license to be legally driven on the road. What’s more, its rear-opening door – complete with fold-out ramps – allowed it to be used by those with disabilities, thanks to the hand controls. It could even fit through a doorway, meaning you didn’t need the luxury of a garage or off-street parking to store it.

The BUBU Shuttle-50 was quickly joined by the BUBU 501 in the same year, a smaller, sleeker model that still only featured a 50cc engine and three wheels, albeit with the addition of a steering wheel. Three years later, the BUBU 505-C joined the range, which mimicked a quarter-scale Morgan Roadster. Mitsuoka shifted into full-size vehicles from the late 1980s onwards, but their microcar vision remained part of their model range up to 2007.

Every vehicle – despite looking obscure even by Mitsuoka standards – served a very important role that even kei cars couldn’t fulfil. Not only were they even more convenient for navigating Japan’s (often) tiny roads, but a moped license was considerably cheaper to obtain than the equivalent car one. While sales were never really booming, the microcar market went from strength to strength right until the late ’80s when a regulation change would all but seal their fate. Aside from safety now being quite important, microcars would now require a full driving license to operate, dramatically slashing their appeal.

However, decades later, there’s at least one man in Japan who has made it his life’s mission to carry on the legacy of this bizarre era of Japanese motoring: Wakayama-based Kaoru Hasegawa.

“I got my first microcar nearly 30 years ago,” Hasegawa-san proudly states. “I have always enjoyed small vehicles, and I was given my first microcar. It had been abandoned in the corner of a car shop out in the countryside, so I spent time restoring it and started driving it around. It was so much fun, and the reaction from other people was amazing. I knew I wanted another microcar, so I started looking around and researching their history.”

Despite thousands of microcars being sold across Japan, tracking down a good, working model is becoming as difficult as unearthing rare supercars – mainly because most people bought microcars for quick and easy transport rather than something to cherish and collect. For Hasegawa-san, he knows this is half the appeal, too. Many of us are familiar with the BMW Isetta and Peel P50 – both sold throughout Europe in much larger numbers – but what makes the Japanese models even more desirable is how much smaller and rarer they were in comparison. Hasegawa-san’s collection now features more than 10 different models, and despite being three decades deep into his obsession, he’s still on the lookout for more.

“When they were new, microcars could be driven with a moped license, so they sold very well,” he adds. “Especially among housewives, as they had been designed to allow people to move quickly with luggage or shopping in all weather conditions. They were much cheaper than a car and could be stored in a normal house easily. But when the new law was passed, meaning that owners needed a driving license to run them, the sales stopped and dealers turned their attention towards kei cars instead.”

Hasegawa-san is more than just a collector of these oddities. For years, he’s shared his love for them across social media, and it wasn’t long before he was being inundated with messages from intrigued car fans trying to decipher what they were looking at or likeminded microcar enthusiasts that – in many cases – assumed the early Mitsuoka BUBU models would never be seen again. Hasegawa-san’s collection expands beyond Japanese cars, however. Two of his cherished models include the Italian Cassalini Sulky and All Car Snuggy Charly, and yes, those are the actual names. Given the global interest his humble little collection had gained, Hasegawa-san decided it was time to create an actual museum for his microcars. That might sound like a vast and expensive project until you realise that all of his collection fits comfortably in a regular downstairs garage.

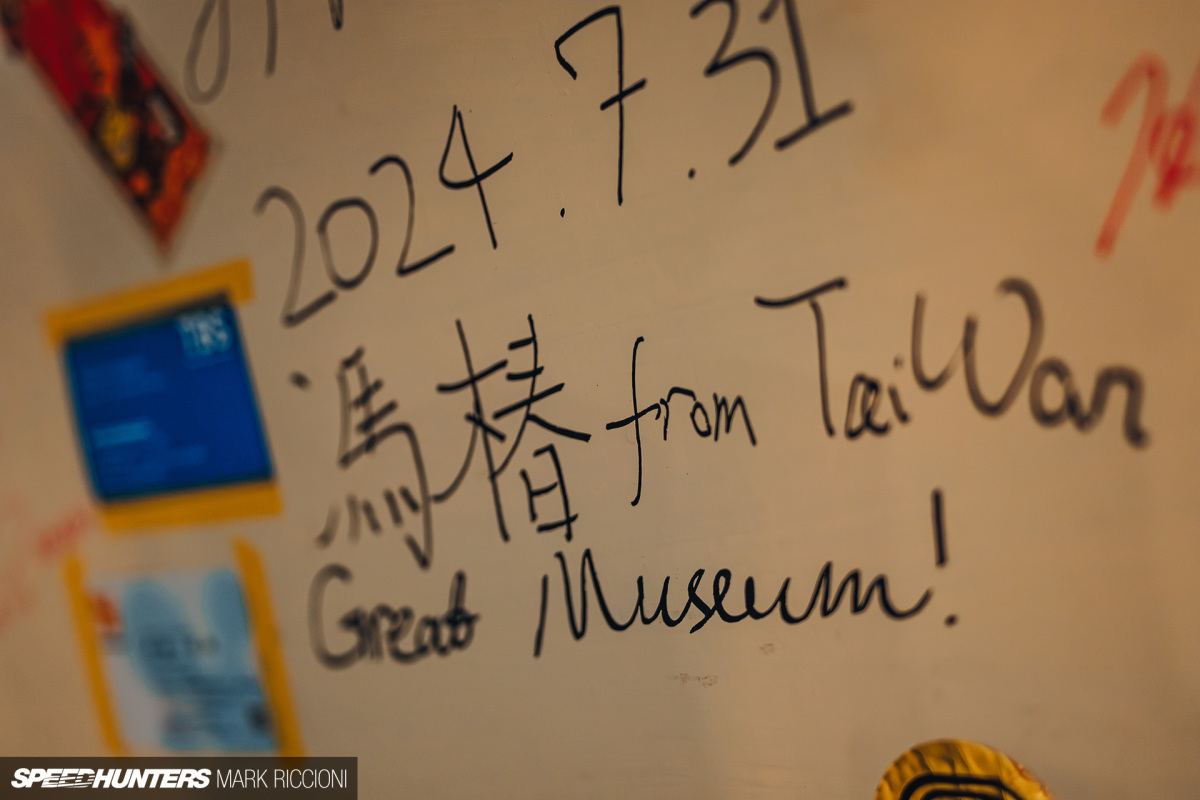

“I created the WAZUKA Microcar Museum because of the messages I kept receiving on social media from people wanting to see the real things,” Hasegawa-san adds. “There are many car museums in Japan, but there is no museum anywhere that specialises in microcars! So, I thought I would make one myself. All of the cars on display are in good, original condition while also being the models produced in the least numbers. I have travelled all across Japan to find them, and the friends gathered here with me were all enthusiasts met along the way.”

Rather fittingly, the WAZUKA Microcar Museum is located on a tiny street, crammed into a tiny terraced house with the upstairs living quarters littered with tiny memorabilia. It is completely unassuming on the outside, but its charm is only matched by the quirky vehicles it houses behind the wooden-slatted garage door.

Despite this, Hasegawa-san regularly hosts microcar gatherings by inviting friends and enthusiasts including Sinchirou Kubo and his Morgan-like BUBU 505C, Kai Kuramochi who has stretched his Casalini Sulky to carry passengers, and Takayuki Teramura whose Casalini Sulky is slammed so low to the ground it’ll beach on any speed bump if he doesn’t approach it fast enough.

These four owners and their cars will shut down any street with intrigue and crooked necks more than any fire-spitting Lamborghini could dream of. All four will fit in a single 7-Eleven parking bay, and, providing you go nowhere near a highway, their top speeds can vary between 65km/h and 85km/h depending on wind direction and road gradient. They are unlike anything else you’ll see on the roads, and their intrigue captivates just about every age and generation.

“We don’t get many tourists down here!”Hasegawa-san laughs, which is unsurprising given it’s a seven-hour drive from Tokyo and two hours south of Osaka. “But my goal is to tell everyone about the museum and show them the history of the microcar. I am always looking for more cars to add – it is half the fun with microcars because they often end up in the most obscure and unusual places. So to bring as many together as possible – and keep them in good usable condition – is a dream for me that I will continue to live out as long as I can.”

Kaoru Hasegawa’s WAZUKA Microcar Museum is located in the Kainan region of Wakayama, Japan. To arrange a visit, you can message him at @kaoru.bubu on Instagram.

Mark Riccioni

Instagram: mark_scenemedia

Twitter: markriccioni

mark@speedhunters.com

Comments